Episode 49: The Willing Bride

The double marriage between the Habsburg and Spanish dynasties organised in the creation of the Holy League in 1495 was part of a larger plan driven by the Spanish monarchs to create a general European-wide alliance against the French. To further these aims, Ferdinand and Isabella also arranged for their other children to marry into the Portuguese and English royal families as well. Such good family planning, however, was not to yield anywhere near the results that Ferdinand and Isabella sought. In this episode we will track the tumultuous journeys leading up to the weddings which brought Spain and the Low Countries together, the devastating repercussions the Spanish monarchs’ religiosity would have for the Jews of the Iberian peninsula, as well as a series of untimely deaths which would see the Spanish succession repeatedly shuffle down the line. When the music stopped in this dynastic game of musical chairs, Philip the Handsome and Joanna of Castile’s five month old baby son, Charles, would found himself perched on the stool which held possession of a ridiculous amount of Spanish, Imperial and Burgundian titles, all of which would eventually make him the most powerful person in Europe.

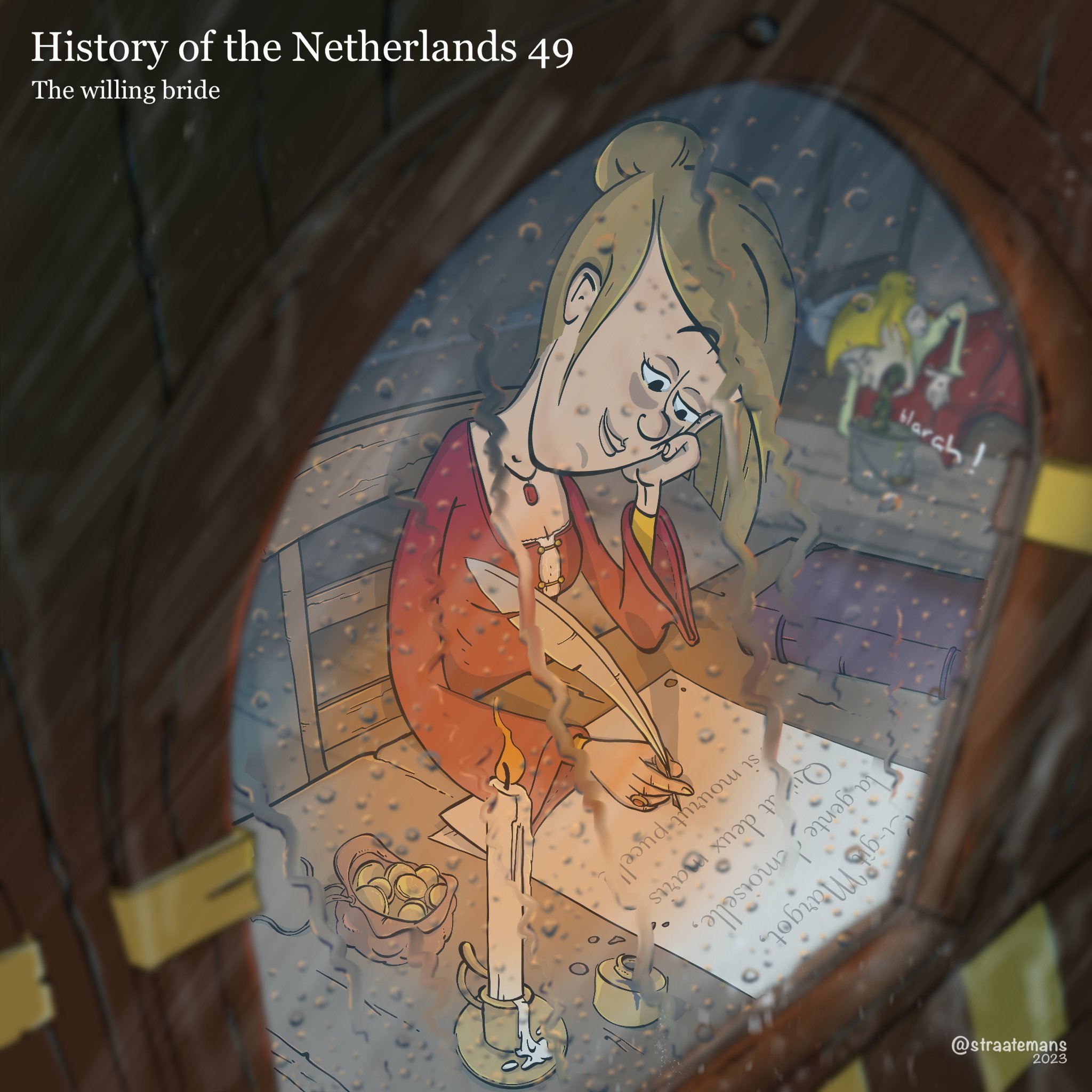

Episode artwork by Steven Straatemans

Ferdinand and Isabella marry off their children

On November 5, 1495, two proxy marriages were conducted in Mechelen in the time-honoured tradition of procurated knee-touching. The first bound Prince Juan, the crown prince of Castille and Aragon to Margaret of Austria, Emperor Maximilian’s daughter and former “Queen-to-be” of France. The second saw Maximilan’s son, Philip the Handsome, Duke of Burgundy, married to Prince Juan’s sister, Joanna. After this, the Great Bastard of Burgundy, Anthony - who, remember, was one of Philip the Good’s many bastard children, Member of the Golden Fleece and was still a highly influential figure at the age of 75 - went down to Valladolid to perform this right on behalf of Philip, in early 1496. As everybody had learned from Maximilian’s failed proxy-marriage to Anne of Brittany, these ceremonies were as good as useless if somebody else rocked up with enough swords to shout ‘I object!’. To make it all official, the happy couples would still need to meet up in real life, tie the knot in person, and then hopefully consummate the whole thing and produce more heirs to whatever territories they were due to inherit themselves, as quickly as possible. We will get to that shortly.

As important as these two marriages might be for our particular interest (the Netherlands), they were actually part of a wider web of marriages which were being arranged by Ferdinand and Isabella which cemented the connections between their newly consolidated Spanish kingdoms and other European powers. Ferdinand and Isabella had five children who had survived beyond infancy and into marriageable age. They were, in the order by which they were born, Isabella, Juan, Joanna, Maria and Catherine. We already know what matrimonial fortunes await Juan and Joanna, but what about the others?

The eldest, Isabella, had been married in 1490 to the heir apparent of Portugal, Prince Alfonso. This Alfonso was the grandson of the King of Portugal who had married Isabella of Castile’s half-sister and gone about contesting the Castilian succession which we spoke about in the last episode. The terms of the treaty which ended that war stipulated that Alfonso and the younger Isabella would marry, in an attempt to repair the relationship between Portugal and Castile. Alas, just a year after their marriage, Alfonso died in a horse-riding accident, leaving Isabella a grieving widow and the link between Portugal and Spain severed. It would be mended, however, when Isabella was married to the new King of Portugal, Manuel I, in 1497. The terms of that marriage would have dire consequences for a significant minority of people in Portugal however, who had already been forced out of Spain because of religious persecution.

Expulsion of the Jews from Spain and Portugal

In the previous episode we skipped over the extreme religiosity of Ferdinand and Isabella and, as much as we would like to skip over this forever, it is going to become an ever more defining part of the history we are trying to tell. So we need to start letting it in, bit by bit. Much like we already saw in the Low Countries, in the 14th century there was a deepening of Jewish persecution and social isolation in Spain. In 1391 there had been brutal pogroms against Jews in Spain and, as a result of this and subsequent atrocities, many Jews had converted to Christianity in the following years. These people were known as conversos. Being conversos did not guarantee them safety from the suspicions of religious fanatics, however, who remained deeply distrustful of the growing power and social status of conversos and would accuse them of being Christian purely in name, but still practising Judaism in secret. Those who did keep their faith secretly were (offensively) named Marranos, though these days the more politically correct term used in academic writing is crypto-jews. In this unstable religious atmosphere and in the midst of the succession war in Castile, Isabella and Ferdinand were keen to stamp their authority on their newly consolidated kingdoms. They wrote to Pope Sixtus IV in November, 1478, asking for permission to root out heretics amongst the conversos. Two years later, the first two inquisitors were named, with this eventually developing into a powerful judicial body under Isabella’s personal confessor, Tomás de Torquemada. To quote François Soyer in his book “The Persecution of the Jews and Muslims of Portugal”: “there followed a period of intense repression of the conversos. Hundreds of conversos were arrested, put on trial and found guilty of having relapsed into their former faith”. Over the next two decades, thousands of people were burnt to death, imprisoned and/or had their possessions confiscated which, in and of itself, brought vast sums of wealth to the crown.

On March 31, 1492, Ferdinand and Isabella issued the so-called Alhambra decree, in which they resolved “to order the said Jews and Jewesses of our kingdoms to depart and never to return or come back”. This was to be done by the end of July that year. The exact numbers here are impossible to determine exactly, but it’s estimated that about 200000 people converted to Christianity following this decree, while between 40000-100000 people left Spain. Many of those who fled Castile found refuge in Portugal, even if circumstances there were often as hostile as the ones which they had just left. The then King of Portugal, João II, allowed 600 families to stay (for a sum, of course), while the rest would be given 8 months to arrange their departure from Portugal too. When João died heirless in 1495, the crown of Portugal went to his cousin, Manuel I. Isabella and Ferdinand wanted to reestablish dynastic ties with Portugal and so wanted their widowed daughter, Isabella, to marry him. But there was a catch.

According to some accounts, the younger Isabella strongly believed the influx of non-Christians into Portugal was an offence to God and that she would only agree to the marriage if the Jews and so-called heretics in Portugal were kicked out of that land too. Others, such as the Venetian ambassador to Burgos, emphasised the role Ferdinand and Isabella played in this atrocious deal-breaker, saying: “The King and Queen of Spain refused to promise or hand over their daughter to the King of Portugal if he did not first of all expel all the Jews from his realm”. Whatever the case may be, Manuel agreed and on December 5, 1496, he also issued a decree to expel all Jews from Portugal. Two weeks after this, Pope Alexander IV issued a papal bull known as “Si convenit”, in which, in recognition of Ferdinand and Isabella’s efforts in uniting their kingdoms, conquering Granada, expelling the Jews and helping to free Naples, he conferred upon them the title of “The Catholic Monarchs”. The expulsion of the Jews from Spain and Portugal is going to have a large impact on the Low Countries, as many crypto-Jews from the region (and their descendants) will find themselves moving to the Low Countries, of whom a large portion will settle in Antwerp and later Amsterdam. But that is for later episodes.

England joins the Holy League

While all of this was going on, Ferdinand and Isabella were also busy weaving another thread into this complex web of alliances by arranging for their youngest child, Catherine, to marry into the English royal family. Again, this match was politically motivated because Ferdinand and Isabella wanted to bring England into the alliance that had formed against the French, in the shape of the Holy League. Negotiations had taken place for English king Henry VII to join the Holy League when it first started, but he was hesitant to join it because of Maximilian. As you’ll remember from episode 47, one of the many things on Maximilian’s plate was his explicit support of Perkin Warbeck, that random Flemish guy who was going around calling himself the King of England. This had led to extreme suspicion between Henry and Maximilian, neither of whom trusted the other’s intentions (which if you ask me was probably pretty good instinct) and this was something which Ferdinand and Isabella would have to overcome if they were to successfully establish this triple-alliance against France.

To try to manipulate the situation in their favour, Isabella and Ferdinand used their youngest daughter as a marriage prospect for the English monarchy. It took a bit of time to come to terms. Maximilian kept making demands of Henry VII that he would be obliged to attack France if he joined the League, but Max was overridden by the other power brokers in the League who agreed to let him in as long as he did not support France. In return for this, the League would promise to not support France again Henry VII. The end result of these negotiations was that by July, 1496, Henry VII and England had entered the Holy League, and in October of that year a marriage treaty was settled upon which would see Catherine marry Henry VII’s son and heir, Arthur, Prince of Wales. Both Arthur and Catherine were only about 10 years old at this point, however, so the actual marriage wouldn’t take place for a while still. Spoiler alert, this Arthur is going to die before he ever becomes King of England, but Catherine will still become Queen of England when she later marries Arthur’s brother, who will become King Henry VIII. You know him, the one with all the wives, some of whom he beheaded? Well, she is the first one of these wives. Catherine of Aragon.

As for the Perkin Warbeck situation, that problem sorted itself out when Warbeck attempted to invade England in late 1497 with just 120 men, after which he was captured, attempted to escape, recaptured and was then hanged at the end of 1499.

Philip the Handsome goes to Innsbruck to see Maximilian

Now, as we’ve been going through this, you may be thinking ‘alright…Spain, England, the Empire…but what about Burgundy? What about the Low Countries? Remember them?’ Well, when you mix family and politics you are going to get a bunch of issues. As we mentioned in episode 47, Philip had different governmental things to think about in regard to his policies than Maximilian did. Philip was a native prince and had the incumbent expectations of this position heaped on him from childhood. He had been raised by a local nobility that had shown a capacity to revolt against a prince if need be and he had been taught to rule the Low Countries, which, with the increased status of the States-General, was a different proposition than ruling an oligarchic empire stretching Eastward. In his early rule, Philip thus displayed a proclivity to take on his advisors’ opinions readily, but also to cooperate with the States-General. All of this meant that Burgundy’s position within this network of alliances being built against the French should be viewed independently from his father’s. Furthermore, his sister Margaret was by his side. As she will demonstrate over the coming decades of our tale, she was intelligent, capable and not one to just carry out the wishes of her pater familias. As Wim Blockmans and Walter Prevenier put it in their book, The Promised Lands, “Archduke Philip the Fair and his sister Margaret of Austria…resisted pressure from their father, Maximilian. The independent stance of the "natural rulers" enjoyed the warm support of their subjects.”

Maximilian threw his weight around to try and maintain authority over his princely son. The Emperor had based himself in Innsbruck and was visited there from late May, 1496, by Philip. The Archduke of Burgundy was joined by an illustrious entourage which included some of the upper-crust of the Burgundian nobility and members of the Order of the Golden Fleece, such as the Lord of Chievres (Willem de Croy), the Lord of Bergen op Zoom (Jan van Glymes) the Lord of Molenbaix (Boudewijn II van Lannoy), and Engelbert of Nassau, as well the bishop of Liege, and also Philip of Cleves. When they call him Philip-Croit Conseil, this is the conseil. Even though Philip of Cleves had been at war with Maximilian not that long ago, he had always done it in the name of Philip the Handsome and he was once again, though not for much longer, a part of Philip’s court. Also along for the ride was one of Philip the Handsome’s most trusted advisors, his tutor Frans van Busleyden, as well as Maximilian’s right hand man in the Low Countries, Albert of Saxony. Albert of Saxony, remember, was the figurative stick with which Maximilian hit people to get what he wanted. Albert had been waging war alongside Maximilian in Guelders until the uneasy stalemate we spoke about in episode 47 had settled. Philip was making this trip to Innsbruck during that period when Maximilian kept summoning Charles of Egmont to the Reichskammergericht to answer for his supposed breaking of the peace in the Empire, but Charles kept on refusing to go. Albert of Saxony wanted to do what sticks do and go break some bones! Frans van Busleyden, on the other hand, was one of Philip’s innercircle who was promulgating peace with Guelders, thereby frustrating Albert of Saxony, who did not hold back his complaints about this government.

There is no record or account of what exactly Philip and Maximilian spoke about during this time at Innsbruck but, based on the now divergent interests that each had, one can presume it was about Guelders, France, the upcoming nuptials and why the hell is Philip not doing what Maximilian wants? Usual father-son stuff like that, one imagines. At some point shortly after they arrived in Innsbruck, Philip dismissed Frans van Busleyden for a period of four months, as well as other members of his council who were pro-France and therefore pro-peace with Guelders. Busleyden was replaced by Jean Carondelet, who had been Maximilian’s chancellor. In this, it is evident that Maximilian still very much saw the Low Countries as his personal domain even though Philip was the Archduke. Max must have been satisfied that he was seemingly bringing Philip more closely to his point of view and away from those of his councillors.

Johanna of Castile arrives in Zeeland

The satisfaction he felt must have increased when, in October, 1496, the actual, real life, not-proxy marriage between Philip and Joanna took place. You know, the one where they get to touch more than just knees! Joanna’s trip to the Low Countries had proven to be quite an ordeal in and of itself. Due to the hostile relations between the Holy League and France, it was not exactly possible for Joanna’s wedding procession to simply march its way across land from Spain, through France, up to the Low Countries. Instead, they needed to go by ship. But you can imagine how potentially fraught with danger this was, not only for Princess Joanna herself, but also for the whole network of alliances that this marriage was crucial to. They could be attacked by the French and possibly killed or captured, either of which would be ruinous for the Holy League. As such, a massive fleet of around 130 ships, led by the Admiral of Castile, was assembled in Laredo, just west of Bilbao. There, the Infanta Joanna and her mother, Isabella, bid each other an emotional farewell as she embarked for her life as the new Archduchess, or ‘Archiduquesa’ of our beloved swamp and presumptive Holy Roman Empress.

You know how sometimes people say “it’s not about the destination, it’s the journey that matters”? Well, whoever says that didn’t go on this journey, because this one was terrible. Many historians on this subject describe it similarly, so we’re just gonna quote one of the flowery old ones just for the joy of getting to say words like ‘tempest’ and ‘inclemency’ in what feels like the right setting. This was written in the 1830s by William Hickling Prescott. By the time they got to the Low Countries, the fleet had “...been so grievously shattered, however, by tempests as to require being refitted in the ports of England. Several of the vessels were lost, and many of Joanna’s attendants perished from the inclemency of the weather, and the numerous hardships to which they were exposed.” When they finally arrived in Zeeland in mid September, Johanna was disembarked and met by a group of nobles, but her husband, Philip, wasn’t among them. He was still busy with discussing his future with his father in Austria, which must not have been the kind of reception she was hoping for. Joanna set off to Antwerp, where she waited for a couple of weeks for her husband to show up.

Before we go on wrapping up this part of our story, which we will after an ad break, let’s have a quick look at an example of what an ‘average-person’s’ experience within this whole situation might have looked like. It is believed that the cumulative number of crew in this fleet would have amounted to between 15 - 20,000 sailors and soldiers; the majority being ordinary, lower class men. Again, numbers on this are absolutely not definitive, nor reliable, but based on speculation and almost-certainly exaggerated contemporary accounts. Given the travails of the fleet, it seems that some soldiers and sailors would have also died on the journey there, but for those who were still on board as the fleet limped into Arnemuyden, in Zeeland, in early September, this awful adventure was not over. Because not only was it their duty to bring the Spanish princess, her retinue and her vast amounts of gold and wealth northwards, but to also bring the Habsburg princess southwards for the second part of this wedding doublet. Thus, they had to wait until the important people had decided that the journey was ready to be made. In his description of this journey and the wedding, Burgundian court chronicler Jean Molinet spends his usual amount of words (i.e. almost all of them) waxing lyrical about the luxurious fashion and fineries on display by all of the pompous people at the party and the entire build up towards the wedding. That he finds any space at all (amongst all this talk of frivolity) to mention the plight of these common sailors and soldiers, who had been left languishing in Zeeland while this party happened, is indicative of how extraordinarily horrific their experience was.

In Molinet’s words, as translated in the book Antwerp 1477-1559: “when winter came and the north wind swept the land, they marvelled at the cold and blew on their fingers and complained bitterly, so that when a day came a little warmer than before they asked if winter had passed. Either the change of air or of food or the thinness of their clothing or some other cause brought on a pestilence and three to four thousand of them succumbed”. Yes, if you did not catch that, while this highly political wedding party was going on, thousands of Spanish sailors and soldiers were waiting around, dressed in clothes probably more suitable to Zaragoza than Zeeland, while some sort of disease ripped through their number and killed them in their thousands. I really like that quote because, having worked in Netherlands tourism for years I can really relate to the imagery. Up until the pestilence part, Molinet pretty much describes every Spanish tour group I’ve ever seen here; standing around in inappropriate clothes, blowing warm air into their hands, wondering if winter is over yet… in October. Also just worth chucking in here that it is believed the disease which ripped through the Spanish ranks in Zeeland was syphilis, supposedly brought to Europe by Spanish sailors who had raped or had sex with indigenous people in the Americas during Colombus’ missions there. Although this view of syphilis’ origin in Europe has been challenged in recent years, this incident in Zeeland has gone down as the first recorded outbreak of syphilis in the Netherlands and is one of the reasons why the disease was known in Dutch as the “Spanish pox”.

Margaret of Austria gets stuck in Southampton

Philip and Joanna’s marriage was made fully official in the town of Lier on October 20, 1496. Once that was done, the time had come for Margaret of Austria to put those freezing and syphilitic Spanish soldiers and sailors in Zeeland out of their misery and make the return voyage to Spain to do her part in the double marriage and complete her nuptials with Prince Juan. All the risks about travelling near France which we mentioned earlier, still applied here. She must have heard all the details from her new sister-in-law and her entourage about just how awful their trip had been and we imagine Margaret must have been quite trepidatious. She certainly had reason to be, as it was midwinter by the time they were ready to go. The first weeks of 1497 saw storms battering the English channel and the Zeelandic coast, delaying the departure by order of the Spanish admiral heading the fleet. It was not until over three weeks into January that, even though storms still threatened, there was enough of a break in the weather to set off. They didn’t get far.

According to Molinet, when the fleet was in the English Channel, the weather turned for the worse and they needed to quickly find safe harbour, doing so in the town of Southampton on the southern coast of England. Luckily for Margaret, Ferdinand of Aragon had been able to rope England into the Holy League, so they didn’t face a hostile reception. We have a few letters to Margaret directly from English king Henry VII that exemplify what kind of good relations could be garnered from the sort of tidy diplomacy that Ferdinand and Isabella had been conducting during the previous years. The following was written to Maragaret in Henry VII’s own hand on the 3rd of February, 1497 “Dearest and most beloved cousin. Desirous the more to assure your Excellence that your visit to us and to our realm is so agreeable and delightful to us, that the arrival of our own daughter could not give us greater joy, we write this portion of our letter with our own hand, in order to be able the better to express to you that you are very welcome, and that you may more perfectly understand our good wishes”.

That’s pretty friendly! And I’m sure she understood perfectly what level of amity she was experiencing. If she didn’t, it was embellished upon a few days later in a second letter from the king, “As we hear that the wind is contrary to the continuation of your voyage, wishing that your Highness would repose and rest, our advice is, that you take lodgings in our said town of Southampton, and remain there till the wind becomes favourable and the weather clears up. We believe that the movement and the roaring of the sea is disagreeable to your Highness and to the ladies who accompany you. If you accept our proposal, and remain so long in our said town of Southampton that we can be informed of it, and have time to go and to see you before your departure, we certainly will go and pay your Highness a visit. In a personal communication we could best open our mind to you, and tell you how much we are delighted that you have safely arrived in our port, and how glad we are that the (friendship) with you and our dearest cousins, the King and Queen of Spain, your most benign parents, is increasing from day to day.”What a charming cat. She’s on her way to get married! ‘Nah, c’mon. Why don’t you just stay here…hang out in my kingdom a while. We can get to know each other.’

Despite the King’s delight and invitation, Margaret was keen to get to Spain and numerous attempts were made to get going. One of these resulted in the ship that she was actually on ramming into another as they attempted to leave the port, so that she and her ladies-in-waiting had to be put on a kind of life boat and rowed dangerously into the wind, in what must have been a genuinely terrifying experience, back to Southampton. Eventually, however, the fleet was able to get out of the coastal waters and make their way to the Bay of Biscay. Unfortunately for Margaret, however, her ship became separated from the rest around the time that the weather completely calmed down and they were left languishing, floating around without wind in their sails. But then, the weather roared back into life, in a worse storm than what they had previously gone through. For a nice description of this, let’s go to Jane de Jonghe: “For days the Spanish seamen fought for the life of their crown princess. No one on board but had taken leave of his own life. Even Margaret.” This means that everybody thought they were going to die.

Margaret turns to poetry

We haven’t really mentioned it up until this point, but Margaret of Austria was well educated, witty and something of a wordsmith. She really enjoyed writing poems. One academic Peter J Eubanks goes so far as to say that “a careful examination of Margaret’s poems demonstrates that her meter, style, emphasis on the infinity of suffering, and insistence on the act of writing as an arbiter of immortality” means that she should be classed amongst the “rhetoriqueurs”. The “rhetoriqueurs” were a renowned group of poets in Burgundy and France from this period which includes such illustrious members as chroniclers we have quoted time and again, Georges Chastellain and Jean Molinet. So during this storm, staring her mortality in the face, Margaret turned to writing in order to process it. Jane de Jonge continues describing this moment of existential doom: “And in the midst of her sick, desperately wailing ladies in waiting, she was able to summarize her own short existence as a princess with refreshing mockery in a two-line-epitaph, which, it was said, she had someone bind to her hand, together with a purse of gold pieces for a royal burial”. So she wrote a short poem and then tied it to her hand with a bag of gold so that if she died and her body was found floating somewhere, whoever found her would know what to put on her grave. Remember that writing was, to her, an expression of immortality. So what immortal essence of herself did she want the prevailing world that endured beyond her miserable death to know about her?

“Here lies Margaret, the willing bride;

Twice married, but a virgin when she died”

Bearing in mind that this has been translated from old French into a more modern English, it’s still a brilliant snapshot of authenticity coming from a contextual period that is so often littered with obtuse, superfluous language such as what we saw in Henry VII’s letters to her while she was in Southampton. This is real, and it can be read a couple of different ways. It can be seen as a teenager staring at death and being sad about the fact that she had never gotten to experience sex. Or, we can look at it in the context of her being a young, noble woman, raised with the understanding that her obligation was to breed and produce more nobles, which socially had to happen via marriage. Now, as she stared into the brink, what she saw was that in her young life she had gotten through the boring and tedious part of the process, TWICE, but had failed to fulfil her duty to reproduce. Perhaps there is a little bit of column A and of column B. Either way you look at it, it’s funny and charming and I don’t think many people in a life threatening situation would have the mental capacity to sit down and write a really witty poem as they’re dealing with the stress of it all. And in French too!

As you might have guessed, Margaret’s self scribed and somewhat whimsical elegy never had to be put to use. The storm passed and, despite their worst fears, the ship stayed afloat. In March, 1497, to everybody’s great relief, the Spanish monarchs received word that the new Crown-princess’ ship had limped, unexpectedly, into the port of Santander, not too far from where they were presumably aiming, Laredo. Arrangements were made and the infante Juan, with his father Ferdinand and a large retinue that included clerical big shots who were there to bless it all, set off to meet Margaret.

Juan and Margaret marry

Juan was, to put it nicely, not very robust. He had a frail constitution and was exhausted or fell sick easily. Historian Samuel Sánchez y Sánchez writes about this in an essay titled “Prince Juan and Calisto”, in which he explains when Juan was suffering from some kind of illness in 1491, his doctors recommended to his parents that the best course of action was for the young crown prince to eat a diet of… turtles. The problem was that there weren’t enough of them in Castile, so King Ferdinand wrote to his chief advisor in Valencia saying “The turtles that were sent to the illustrious Prince our son are finished and it is a great inconvenience that they do not exist, due to the great benefit that experience shows to do in his person”. He then goes on to order him to scour the city of Valencia looking for more turtles and to send “forty of them of them each month and send them to us safely without dying” and that if there aren’t enough in Valencia, to send for them from Majorca instead! I guess when the ones in Majorca ran out, he’d go scouring Italy instead. Lots of turtles there, like… Leonardo... Or Donatello… Couldn’t resist. Anyways back to it. According to Juan’s tutor, Italian humanist, Spanish diplomat, chaplain to the monarchs and, from 1500, official chronicler of the Spanish court, Pedro Mártir de Anglería, despite his frailty Juan was an old head on young shoulders. Taking into account the conventional etiquette of flamboyant flattery displayed to royals, in a letter to Juan, Mártir wrote “Hail to the old man who was surprisingly young.” He tells him that every person with whom the prince engages, “whether nobles of class or servants destined to serve the humblest of fortune, praise, extol and admire thee.” I’m not sure whether the people wading around in ponds in Valencia desperately looking for turtles upon royal decree were extolling the young prince.

Be that as it may, Juan, the Prince of Asturias, goes down in history with a pretty good reputation as being thoughtful and considerate and beloved by his subjects. But he also represented something which his parents badly needed to be beloved; he was the embodiment of the united Castile-Aragon powerhouse that now also included whatever fortunes awaited the Spanish in their proclaimed new distant territories. The court-life he had grown up in was solemn, religious and awash in pompous etiquette. This differed from the court life that Margaret and her retinue were used to. Burgundian and French courts were more jaunty. William Hickling Prescott, again in wonderful 19th century language, described the task of the Low Countries folk who had accompanied Margaret to Spain as them needing to “...reconcile themselves to the reserve and burdensome ceremonial of the Castilian court, so different from the free and jocund life to which they had been accustomed at home.” Margaret got a pretty quick taste of the burdensome ceremonial stuff that the Spanish were into. Her entourage made their way to greet the King of Aragon and his son and heir, her husband - remember they were already married by proxy - Prince Juan, who apparently was, himself, not a fan of …fanfare and was already exhausted from the trip they had made. Juan watched his bride approach his father and, according to protocol in which she had been carefully tutored, kneel and kiss his hand, before she did the same to Juan. According to Molinet, at this point: “clarions and trumpets, tubas and horns thereupon let forth a blaring fanfare so loud and high that one could not have heard the Lord thunder.” This was a tremendous moment indeed!

Over the next few days the entire entourage went south to Burgos. Margaret was brought to the town hall, which she entered walking under a baldaquin, which is a big, ceremonial canopy that all the Governors of Burgos had to hold up above their heads. More ostentatious ceremony ensued. She entered the Town Hall and there, met Queen Isabella and her swag of attendants. Margaret did as convention demanded and, kneeling, kissed Isabella’s hand. Then each of Margaret’s ladies-in-waiting had to do the same. Then, each of Isabella’s ladies-in-waiting had to kiss Margaret’s hand. That’s fine. Except there were 90 of them. 9-0. It must have taken forever. They are probably still going. Honestly though, there is a real chance she got some kind of friction burns, so often was her hand grazed by some random Spanish woman’s lips. Honestly, we humans…we have spent so much time in history engaging in just… the wackiest stuff. Anyway, Easter soon followed and she got to know her family and even charmed Isabella, shocking the Spanish court regulars by the informal and jovial nature with which she engaged with her new mother-in-law, the absolute monarch of Castile who, along with her husband, quickly became fond of Margaret. On Easter Monday the young couple undertook another wedding ceremony - just close family and friends - before setting off for a week’s honeymoon, literally just to have some time to themselves. This was no doubt so they could get on with their private royal duty, which was to produce an heir, before undertaking their public one. This latter duty was to entail firstly another wedding, before spending months travelling around Spain, making joyous entries, taking fealty from countless towns and cities and estates, feasting at banquets, applauding at tournaments, attending festivities and just generally frolicking around. All of this frolicking by the royal couple added to the overall public vibe of excitement. Like so much of Europe, Spain had seen its share of local wars, brutality and deprivations over the previous decades and, now, here was the young couple who would be the monarchs of the peaceful, prosperous and united Iberian kingdoms into the future.

Juan suddenly dies

The problem is, this was all just too much excitement for the Prince of Asturias, Juan. Margaret’s husband’s already frail health waned ever more. There is a fair bit of discussion that this was due to that classic affliction that we mentioned in the previous episode; ‘immoderate coitus’. Pedro Mártir de Anglería, Juan’s tutor and aforementioned chronicler, goes quite hard on this angle, though we should definitely take all of this with a grain of salt. Mártir wrote of Margaret: “if you saw her, you would have an idea that you were looking at Venus herself. What in beauty, size and age Mars could have wished for Cytherea, just as she was sent to us from Flanders, without disfiguring with any makeup, without dressing up with any art. You would say that it was Oritia escaped from the hands of the frozen Boreas. But we tremble at the thought that all this may one day bring us unhappiness and perdition to Spain.” He then later goes on to say “Our young man [meaning Juan], burning with love, got his parents to arrange his marriage bed, finally reaching the desired hugs with Madame Margarita. But only a couple of months had passed and already the multiplication of the desired embraces and the continued boiling of pleasure had alarmed the prince's doctors and King Ferdinand himself, although not the Catholic queen, accustomed to the natural robustness of her husband”. Indeed, so concerned were they at his hyper-exhaustion, that Juan’s physicians at one stage begged Isabella that he be separated from his young, voracious and vivacious wife, but Isabella refused, apparently saying that “it is not convenient for Men to separate those whom God united with the conjugal bond”. The Catholic Monarch Isabella wasn’t going to let people interfere with her son’s godly union. It seems at the very least that, since arriving in Spain, Margaret had made sure that the lament that she had written when she thought she was going to die at sea would never be a factor again. She made sure that she would not die a virgin. Strangely, though, if these rumours are to be believed, her husband would die from too much sex.

In late September 1497, about 6 months after Margaret’s arrival in Spain, Prince Juan contracted a fever, probably from tuberculosis. Ferdinand and Isabella found out that Juan was deathly sick while they were on the border with Portugal celebrating the wedding of their eldest daughter, Isabella, to Manuel, the king of Portugal. This was the marriage that had come at the cost of thousands of people being displaced because they were Jewish or had been identified as such. Upon hearing the news of Juan’s illness, Ferdinand rushed to his side, arriving just before he died.

But that was it for Juan. On October 4, 1497, Juan, the crown prince of Castile and Aragon and just 19 years of age, succumbed to his illness. For the second time in her young life, Margaret of Austria went from as-good-as wearing a Queen’s crown, to being cast away from the state’s governing apparatus through zero fault of her own. There was a prolonged, deep and grievous state-wide mourning, although there remained some cause for sustained hope. Margaret, now widowed, was pregnant. Perhaps there would be a new heir. Tragically, though, this hope would be extinguished not long after when her child, a daughter, was prematurely still-born. This poor woman. Margaret would stay in Spain for a short while longer, seemingly continuing to be treated with love and kindness by her no-longer parents-in-law, before she would make her way back to the Low Countries in late 1499. Even though she had not, in the end, given birth to the heir of the Spanish kingdoms, in the strange way that things work out, in a few years she will come to be the guardian of the heir anyway.

Tragedy after tragedy in Spain leaves baby Charles as presumptive heir

And those strange ways went something like this: After Prince Juan died, his elder sister Isabella, the Queen of Portugal, now became the Princess of Asturias and heir presumptive to Castile as well. There was debate in her father’s kingdom of Aragon about whether a woman could inherit the crown there, but we are not gonna get into that! Around this time, however, the Catholic Monarchs received another piece of information. Their new son-in-law Philip the Handsome, to whom they had wed their second daughter, Johanna, had begun to style himself as Prince of Castile, by virtue of his marriage to Johanna. This sent a shudder that has been described as ‘disgust’ through Isabella and Ferdinand. Johanna was the next in line after Isabella - although around this time Isabella also became pregnant. Nonetheless, this foreign Habsburg/Burgundian prince was now frighteningly close to the Spanish thrones.

Isabella and Ferdinand hurriedly set about getting the Portuguese monarchs, their daughter Isabella and her husband Manuel, to bring their retinues to Toledo and do all the necessary oath-swearing that would ensure their right to succeed Isabella and Ferdinand in Castile. They then went to do the same in Aragon, and this is where there was a bunch of contention about the whole female succession matter. Again, not gonna get into it, other than to say it became a protracted, frustrating process, stretching into late August, 1498. No conclusion was arrived at, nor was any needed in the end. On August 23, Isabella, the Queen of Portugal and Princess of Asturias, went into labour and gave birth to a son, Miguel. An hour later, however, the younger Isabella promptly passed away in the arms of her mother, the elder Isabella. Losing a second child in the space of a year must have been heartbreaking.

Baby Miguel’s male-ness certainly solved their issues of succession in Aragon. In him they had not only a male heir to the crowns of Castile and Aragon, but also to Portugal. This really could have been a watershed succession for the Iberian peninsula. The Catholic monarchs quickly went about having all the same oaths of fealty made to him and themselves sworn in as his guardians. Their new grandson was the perfect foil to the evidently growing ambitions of Philip the Handsome, over there in the Low Countries, styling himself as the Prince of Castile.

But, for Ferdinand and Isabella, the year 1500 would be an emotional one. They got another grandson - a Flemish one, even! He was born in February in Ghent, to Joanna and Philip, who named him Charles (after his great-grandfather, Charles the Bold). Over in Spain, however, later that year yet another tragedy struck the royal family. Miguel, the infant heir to the three Iberian thrones, died shortly before his second birthday. No amount of fealty can stop that happening. To keep the bonds between Spain and Portugal going, in October 1500 Isabella and Ferdinand’s last remaining child, Maria (you thought we forgot about her!) was married to Manuel I of Portugal. But young Miguel’s death meant that the right to succession in Castille and Aragon - as is tradition! - passed on to whomever was the next in line on the conveyor belt of ‘potential Spanish monarchs who are alive’. This was, of course, Isabella and Ferdinand’s third child, the new mother of the baby Charles, the wife of Philip the Handsome and the Archiduquesa of Burgundy, Johanna.

Joanna’s baby, Charles, was already from birth the presumptive heir to Burgundy and the Holy Roman Empire. With the death of his cousin, Charles had now also acquired the presumptive rights and titles to the crowns and thrones of Castile and Aragon, along with the Spanish self-proclaimed (and Pope-verified) rule over the Americas. And he wasn’t even 5 months old yet! When it came to this infant, who would grow into Emperor Charles V, the world really was his oyster. His sudden and, you might say, unplanned inheritance would bring vaster regions of the world together under single, European rule than had ever been seen before.

Lyrics to “Ball of the Burning Men” by Exchanger

Verse 1

Tonight we celebrate, for some maid of the court

Will bind herself to man, for the second time, the young tart

Tonight we humiliate, have fun, eat well, be drunk, make noise

As the tradition dictates, for the twice wed goose

Chorus

The king rules surrounded by fools

They came to the feast in the guise of a beast

Madness reigns as they’re bound in chains

Let the dames shield you from the flames

It’s the Ball of the Burning Men !

Verse 2

The almighty Church frowns upon these pagan rites

They might be kingmakers but did they really think they could change our ways ?

We will pray to the One God and chant with the priests at dawn

But we’ll still dance past the noon and sing the old tunes

Verse 3

Lights out, foul creatures burst into the room suddenly

Exotic monsters to amuse, really the king’s bunch in disguise

Some lesser count has devised this brilliant surprise

Dancers covered in pitch and feathers, which come alight so easily

And so the guessing game begins, among them hides our king

Under which of these grotesque suits is our crown ?

His brother in the crowd can’t wait to find out

Can’t help himself to break the one rule - No fire inside !

For lack of light he grabs a flame - No. Fire. Inside!! No!

Chorus

The king rules surrounded by fools

They came to the feast in the guise of a beast

Madness reigns as they’re bound in chains

Let the dames shield you from the flames

It’s the Ball of the Burning Men !

The king rules surrounded by fools

They came to the feast in the guise of a beast

Madness reigns as they’re bound in chains

Let the dames shield you from the flames

It’s the Ball of the Burning Men !

Sources used:

Chroniques de Jean Molinet, Tome 5

“The Jews of Spain and the Expulsion of 1492” by Norman Roth

The Persecution of the Jews and Muslims of Portugal by François Soyer

“Queen Isabella and the Spanish Inquisition: 1478-1505” by Lori Nykanen

The History of the Jews of Spain and Portugal by E. H. Lindo

“Henry VII, France and the Holy League of Venice: the diplomacy of balance” by J. M. Currin

The Promised Lands by Wim Blockmans and Walter Prevenier

Philips van Kleef by A. de Fouw.

Margaret of Austria: Regent of the Netherlands by Jane de longh

History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella the Catholic by William H. Prescott

Review of “Bijdrage tot de kennis van de geschiedenis der syfilis in ons land, J.W. van der Valk, 1910” by P.C. van Voorst Vader

Calendar of letters, despatches and state papers relating to the negotiations between England and Spain edited by G. A. Bergenroth

“Marguerite D’Autriche - Grand Rhétoriqueuse?” by Peter J. Eubanks

“Prince Juan and Calisto” by Samuel Sanchez y Sanchez

Isabella: The Warrior Queen by Kirstin Downey

‘The Burgundian Netherlands, 1477–1521’ in The New Cambridge Modern History, chapter by C. A. J. Armstrong